PARTNERSHIP IN PRIMARY CARE

Dr. Yan Xiao and his collaborators are reimagining the patient-provider relationship, from nixing the term “patient” to expanding telehealth.

By Forrest Meyer

Dr. Jody Greaney uses intradermal microdialysis coupled with laser Doppler flowmetry to assess the mechanisms contributing to the regulation of cutaneous microvascular function. Her laboratory is currently investigating the mechanisms underlying neurovascular dysfunction in human depression.

When patients and health care professionals see each other and behave as full partners in the journey to health, all involved can achieve improved outcomes in patient safety and well-being. Researchers in the College of Nursing and Health Innovation at The University of Texas at Arlington are leading a four-year, federally funded project exploring the potential of this partnership model in primary care to improve patient safety in medication management and more.

When patients and health care professionals see each other and behave as full partners in the journey to health, all involved can achieve improved outcomes in patient safety and well-being. Researchers in the College of Nursing and Health Innovation at The University of Texas at Arlington are leading a four-year, federally funded project exploring the potential of this partnership model in primary care to improve patient safety in medication management and more.

The project’s leaders say the key is test-proven designs of behavioral systems and environments—physical and virtual—that can set up these crucial partnerships for the best chance of success.

CONHI faculty members Dr. Yan Xiao and Dr. Kathryn Daniel serve as the project’s principal investigator and co-principal investigator, respectively. As of spring 2021, they have interviewed around 20 Texans aged 65 and older, speaking both English and Spanish, as well as dozens of primary care physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, medical assistants, community pharmacists, and administrative staff from around the country.

The project expands beyond CONHI, with faculty from the UTA Colleges of Engineering, Business, and Liberal Arts also on the team.

“Research in this project is a team sport, just as our model of partnership in patient safety is,” said Dr. Daniel, Associate Professor and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs in Nursing. “The many interviews and focus groups we are conducting in this phase are helping us to triangulate, to look at the same problems and issues from different perspectives. This requires a great deal of teamwork, which will help us arrive at solutions that are most likely to work.”

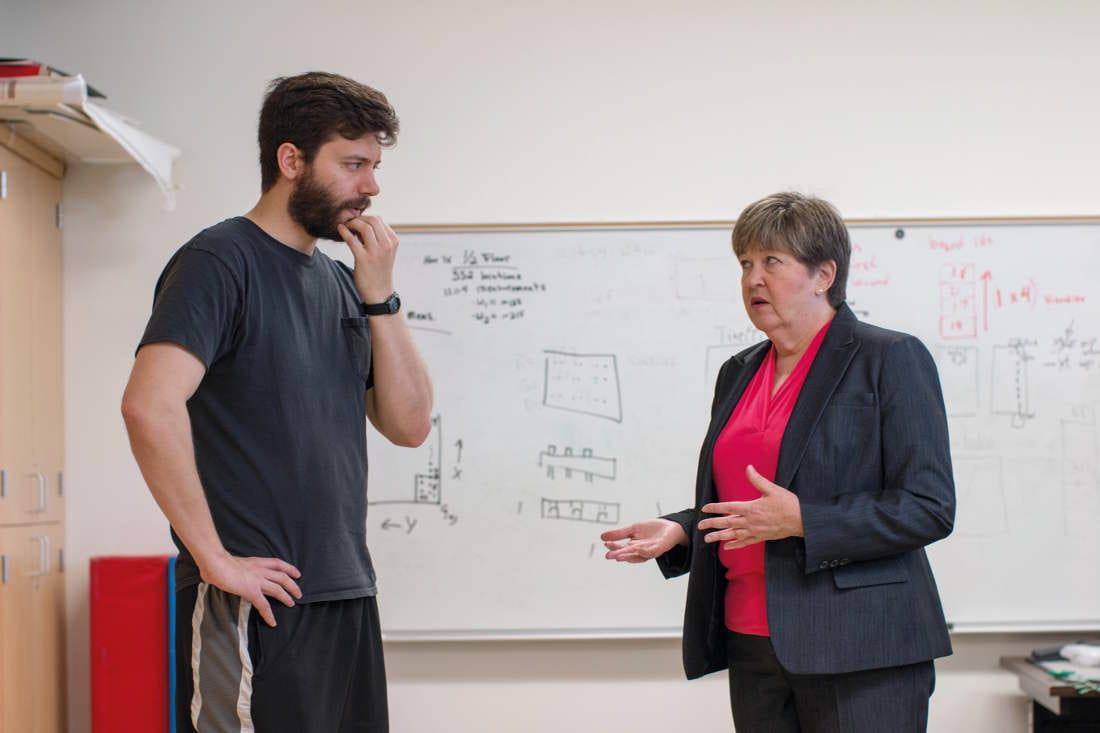

In a separate project, Dr. Kathryn Daniel speaks with an engineering student who is assisting with the mechanics of the SmartCare Apartment. The SmartCare Apartment is a living laboratory apartment in a nearby senior living community that uses state-of-the-art technology to collect information about the well-being of the person living there temporarily.

The multi-site research project being coordinated from UTA is funded by a four-year, $2.5 million grant made in 2019 by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. AHRQ funds a national network of patient safety learning laboratories. In 2020, AHRQ provided the UTA-led project with a one-year supplemental grant that will help researchers assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health delivery systems and methods (such as telehealth) and patients’ ability to manage their medications safely.

“The mentality of health care for quite a while now has been a one-way delivery model. The patient is passive; you are an object of being cared for,” said Dr. Xiao, a Professor in Undergraduate Nursing who oversees the Partnership in Resilience for Medication Safety Learning Lab, or PROMIS lab. “The things that patients receive passively from health care professionals have very little impact on the final outcome.” This is especially true for medication management at home, Dr. Xiao said.

“This partnership becomes a driving force for our interpretation of a new type of medicine. As an engineer, I think in terms of designs of systems. How do you get a system that will operate with the assumption of seeing a patient as a partner and not as some passive recipient? We are trying to get to a place where the health care professionals can do their best part to help patients get better. So, there are many partners involved.” —Dr. Yan Xiao

Up to now, according to Dr. Xiao, the practice for the most part has been, “You as a patient have a problem; you come to me, the health professional; I give you a solution; and that’s the end of the story. But to work in the best way, health care really has to be designed quite a bit differently than a transaction like buying a consumer product.”

In addition to the elderly adult community-dwelling patient participants, the team making up the PROMIS Lab consortium include researchers in public health and pharmacology from The University of North Texas Health Sciences Center in Fort Worth; clinicians in the John Peter Smith system, also in Fort Worth; a human factors engineer, a geriatrician, and a patient services expert from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore; a North Texas primary care research network; and a patient safety advocacy leader who is an expert in patient advocacy and representation.

Dr. Xiao describes the PROMIS lab as an “in situ lab,” dispersed across the several clinics and centers that are part of the project’s consortium. Patient participants and clinicians engage with each other in actual health care encounters that researchers study and assess.

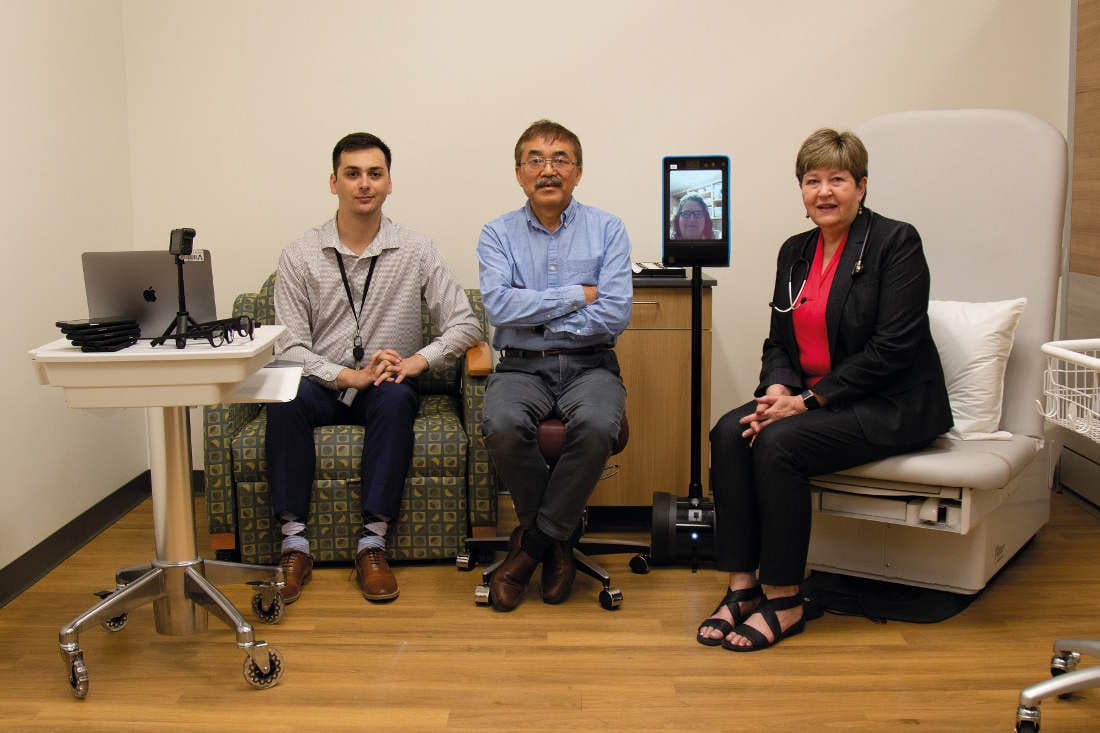

Another key part of this research project, however, is what most people might think of as a laboratory—a single physical location where scientific questions are explored in controlled conditions. The Healthcare Innovation Lab (HI Lab) on the UTA campus is a simulation setting that consists of two exam rooms of different sizes and types, a consultation room, and a participant-patient entry and receiving area. Technology supporting telehealth visits is incorporated in the lab. Jennifer Roye, Assistant Dean of Simulation and Technology, is part of the team, along with other members involved in the design of the HI Lab including behavioral systems engineers and architects.

Noah Hendrix, research project manager, describes the HI Lab as “essentially a near-functional primary care setting.”

“The idea is to be able to use participant-provider simulations to standardize primary care visits and be able to manipulate different variables,” Hendrix said. “The two exam rooms are very different. The smaller one is more of the typical primary care visit experience as you might have it today, and then there’s the larger one, which is more idealized or theoretical in that it is larger and has better equipment, and then we can compare how these two exam room settings perform relative to each other, and where the areas for improvement are.”

Dr. Xiao said selected participants—community-dwelling individuals 65 or older who live at home independently—who would traditionally be referred to as “patients” are invited to the HI Lab to simulate clinic or office visits with their clinician in a partnership.

He said that in these simulated interactions, the term “patient” is avoided as much as possible because it does not fit with the partnership experience they are seeking and because it is a term more accurately associated with hospital stays.

Terminology matters throughout this project. For example, the area in the HI Lab where participants first arrive for their visits is by intention not called a “waiting room,” because the notion of waiting feeds the current dynamic that can make the participant feel like a passive recipient of health solutions that are merely dispensed to them.

“It can feel like you are just there wasting your time, or having your time wasted, while you wait,” Dr. Xiao said. The architect in the project helped design that space to make it a more engaging area where participants might, for example, take part in meaningful educational activities about their condition or about general health and well-being.

The COVID-19 pandemic has, of course, greatly increased the use of telehealth. In many cases, this has made maintenance of key health care relationships possible, but it also has presented challenges for the population being studied because of the barriers to access to telehealth that many elderly people and others face.

For so many older adults, their conception of health care is ‘I need the doctor to tell me what to do.’ They tend not to ask questions … We need to encourage these people by telling them, ‘You have a role here and we need your active participation in this job of helping you to be healthy.’” —Dr. Kathryn Daniel

The HI Lab can study the effectiveness of telehealth interaction by running the experience through different scenarios. In one of these, the patient-participant may live close to the clinic, while their health care professional may live too far away to get to the clinic easily. The patient then goes to the clinic lab and has a telehealth session while sitting in the lab’s well-equipped consultation room. Conversely, it might be the clinician who can work from the lab clinic, and the participant does the telehealth appointment from her or his home. In some situations, the telehealth appointment could take place with neither clinician nor patient-participant being at the clinic lab, but both in remote locations.

If the HI Lab represents the ideal for best practices, then the “real world,” in situ portion of the PROMIS Lab project is a complement to that. Operational clinic practices allow researchers to see how much the envelope of existing parameters and realities can be pushed.

In one part of the project, the PROMIS lab researchers are working with two clinics. One is a small private practice of the type that many of the study participants visit for primary care. The other is a primary care clinic within a large academic medical center.

“We have an opportunity to work with these clinics within the restraints of their spaces and the real conditions of their practice,” Hendrix said.

“Working within what they currently have is one of our goals. We are seeking those interventions that the clinicians and the administrators want, and if they feel confident in those since they’ve been involved from the start in our exploration phase, then they are receptive to trying new things.”

Dr. Xiao concurred. “We try things in real life and see how they work. We design together with professionals working in those clinics,” he said. “‘Will this work for you? Let’s give it a try.’ That is the spirit of the collaboration.”

He adds that AHRQ, the federal funding agency for the project’s grant, “has given us a long leash in exploration of what works and what doesn’t. They have given us as investigators the freedom to go where we think the research will lead. AHRQ is very prescient in thinking that we cannot limit the research to any single component of medication management at home. We should allow a network of researchers to explore many ways and factors that can contribute to patient safety.”

While a primary focus of the project is learning how to minimize preventable errors related to medication use, Dr. Xiao said that medication errors by patients at home are “only a symptom of the lack of partnership” in the wider health care system.

“This partnership becomes a driving force for our interpretation of a new type of medicine,” Dr. Xiao said. “As an engineer, I think in terms of designs of systems. How do you get a system that will operate with the assumption of seeing a patient as a partner and not as some passive recipient? We are trying to get to a place where the health care professionals can do their best part to help patients get better. So, there are many partners involved.”

Dr. Daniel, the project’s co-principal investigator, agreed. “So many players have a piece of the pie in patients’ medication management.”

She has seen this up close in her careers as an academic and a clinician. Early in her career as a nurse, Dr. Daniel spent much of her time tending to the needs of elderly patients. Later as a nurse practitioner, she worked for a decade with patients similar to those in the study. She has both a mind and a heart for this work.

“This is a growing population, and in many ways, it seems to have become a vulnerable, forgotten, and undervalued population,” Dr. Daniel said. “For so many older adults, their conception of health care is ‘I need the doctor to tell me what to do.’”

“They tend not to ask questions and can leave appointments with some lingering confusion. But then they just have to do the best they can on their own at home. We need to do a much better job with patient education. We need to encourage these people by telling them, ‘You have a role here and we need your active participation in this job of helping you to be healthy.’”

The hope reflected in the name of the Partnership in Resilience for Medication Safety Learning Lab is that health care can become its best when every person in the endeavor is empowered to do their part.